Pitch

How to think about it and why it matters.

I’m on the train back from Maastricht to Berlin, the best time to crank out a newsletter that has been brewing in the background over the past week.

This is the second edition of a four-week series on popular music. This newsletter has forced me to live in that world, which honestly has been great. Last night, I was listening for the chords of a couple of songs that were playing at the wedding party I was attending. I was surprised at how much I could figure out just by listening.

I’m convinced that a solid knowledge of movable solfège (which I can get into in a later newsletter), key signatures, and a solid foundation of Roman Numerals (see below) can get us pretty far in terms of understanding songs how songs are built, playing them by ear, and borrowing ideas here and there.

Understanding Pitch

Pitch is a core concept in music. There can be no music without pitch. Even a drummer playing on their own, hitting different snares, rides, and cymbals, produces pitches of some kind.

To give you an example of what actual un-pitched sound, sounds like here’s white noise:

What is Pitch?

If you’ve ever heard a howling ambulance or police car drive past you, you will have encountered pitch in its most basic form: a single note gliding up and down in pitch. Here’s a siren sound I made on my computer, the most basic form of pitch changing over time:

A siren is a distillation of pitch changing in time.

Pitch and Frequency

Pitch is rooted in the frequency of sound waves, and is measured in Hertz. When a keyboard player presses an A key on their synthesizer, the waves emitted travel through the air, vibrating at a specific frequency, until they reach the cochlea of the human ear. The ear perceives this pitch as having a frequency of 110 Hertz, to which we have assigned the value of A2:

If that same keyboard player pressed the next A a bit higher, the synthesizer produces a pitch vibrating at exactly double the frequency, and we hear the pitch of A3 (220 Hertz), which lies exactly an octave higher:

And if they played the next A, higher again, we again double the frequency to 440 Hertz, yielding the pitch labelled A4:

As you can see and hear, pitch works in a way that every time we double the frequency, we hear a note that sounds identical to the previous one but higher. To summarize:

A2 is 110 Hertz,

A3 is 220 Hertz (double 110), one octave higher

A4 is 440 Hertz (double 220), one octave higher again.

To use a metaphor we can all grasp: imagine climbing a staircase in an apartment building where the layout of every floor is identical. Although the new floor looks the same as the one below, you are higher up. In this analogy, each floor you reach represents a higher octave.

Taking the Stairs: Scales

If we take this analogy a bit further we can imagine the piano keyboard to be designed like an apartment building with a ground floor A0 plus six levels A1 through A7. (I’m using the European way of labelling buildings).

The thing is, that the piano has an extra three pitches on top: A#7, B7, and C8. Think of those as being the top floor of the building, with spacious maisonette apartments.

Here’s how we get to the concept of scales. To get from one floor to the next you need to take the stairs. Every staircase consists of exactly 12 steps. The scale is the specific pattern you take up that staircase.

If you take every step up, you get a chromatic scale:

If you skip every other step, you get a whole-tone scale:

The chromatic and whole-tone scales are rarely encountered in pop music, if they are used, they are used more for special effect.

However there are other specific scales, called major and minor, that combine unique patterns of whole-steps (W) and half-steps (H). These are not only ubiquitous in modern pop music, they are the foundation of that same music.

If you follow a specific pattern of W, W, H, W, W, W, H, you get a major scale:

This is the major scale, a ubiquitous pattern in modern pop music. Think of going up a set of 12 stairs, but skipping some while taking others.

If you follow a different pattern of W, H, W, W, H, W, W, you hear a minor scale, which sounds more somber and darker than the major scale:

In summary, while the chromatic and whole-tone scale are quite rarely found in modern pop music, those of the major and minor scale are ubiquitous, so ubiquitous that you cannot think of pop music without them.

Viewed from Outside: Key Signatures

Let’s push this analogy even further. Now imagine there to be not just one apartment building, but a total of 12, and let’s say their facades are painted in different colors. Each apartment building represents any one of twelve key signatures: A, B, Bb, C, Db, D, Eb, F, Gb, G, Ab.

The only way to know which apartment building you’re in is to leave the building itself and take a look at it from the outside.

This mirrors how we perceive pitch. We never know what key signature a given song is in unless someone explicitly tells us, or we check on a piano keyboard, or we have the rare musical ability of discerning absolute pitch.

If the apartment buildings are identical in their construction, then why do we need 12 of them? Wouldn’t merely one suffice? Once we’re in them, they do feel the same after all.

This is a good question, to which there is, unfortunately, no one definitive answer. For the listener, it really makes no difference, but for the musician, it can. It is important to note that key signatures are higher or lower relative to each other.

For example, singers might feel that singing melodies in a certain key fit more comfortably into their vocal range. Recently, my friend Khaleel (6RAJ) told me that certain keys sound better on club sound systems, specifically keys based on E, F, F#, and G. This is in fact a piece of evidence that keys having a noticeable impact on listeners.

In summary, keys have more of an impact on how the musician, songwriter, or producer creates, than they do on the actual listener, who most commonly cannot hear what specific key a given song is in.

One listeners do notice, however, is when we change from one key to another, for example, from A major to D major. This is called modulation, and it’s akin to taking a bridge directly from one apartment building to an adjacent one. But that’s for the next newsletter.

Letters or Numbers?

There are two fundamental ways of thinking about pitch: absolute and relative.

Absolute Pitch: This refers to specific pitches using letter names. For example, A4 is a specific pitch on the piano keyboard. The letter A alone refers to all A pitches on the keyboard, regardless of the octave. This is akin to looking at the apartment building from the outside.

Relative Pitch: This denotes the position of a pitch within a scale using numbers. Relative pitch is contextual; it answers the question, “I can hear A, but how does that A fit into the song I’m hearing?” This is akin to standing inside the apartment building.

To make this concrete, let's see how the note A fits into various major scales. The note “A” can serve different functions depending on the major scale it belongs to:

A major: Scale Degree 1

G major: Scale Degree 2

F major: Scale Degree 3

E major: Scale Degree 4

D major: Scale Degree 5

C major: Scale Degree 6

Bb major: Scale Degree 7

As shown above, the note “A” can be slotted into any of seven different positions, depending on which major key it appears in. To continue our apartment building metaphor, we can think of A as playing different roles, depending on which apartment building we encounter it in.

Melody

Now that we’ve covered the most important concepts of scales and keys, we can actually get to looking at Dua Lipa’s song “Love Again” through the lens of pitch.

Melody is what we get when we add the time dimension to pitch. In other words, melody refers to a a sequence of pitches that occur after one-another.

Let’s look at the opening of the song “Love Again,” first the vocal isolated from the rest of the band:

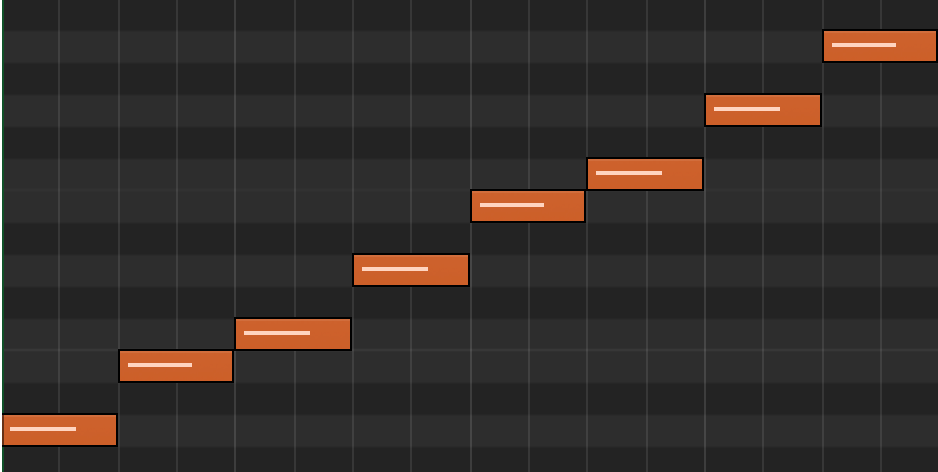

Here’s that vocal melody, transcribed into MIDI by myself:

Here’s that same scale in a piano roll representation:

The melody uses only the pitches contained in the scale of A major.

Notice the similarities to steps in a staircase? Imagine someone jumping up and down the steps in the specific pattern of the major scale.

Chords

Where the idea of melody defines pitches in time, chords define pitches that occur simultaneously. Stretching the analogy, think of chords as being represented by apartments on each floor. Each floor has a total of seven apartments: three large apartments, three small ones, and one tiny apartment that is quite diminished in size. Each floor has the same layout of apartments, we have seven apartments across seven floors, yielding a total of 49 apartments. The different apartments represent the different chords that are available to us: major, minor, and diminished chords.

The way a chord works is that it stacks pitches atop one another. A chord that involves exactly three pitches is called a triad. There are three types of triads that appear naturally in major and minor keys. By naturally, I mean they emerge from the natural property of the scale:

Major Chord: Major Third + Minor Third (M + m). (Large apartment, well-lit and bright.)

Minor Chord: Minor Third + Major Third (m + M). (Small apartment, no direct sunlight, a bit darker.)

Diminished Chord: Minor Third + Minor Third (m + m). (Tiny apartment, no natural light, crammed.)

You can hear that the first chord (major) sounds bright and stable, the second chord (minor) sounds dark and stable, and the diminished chord sounds tense and unstable.

Major, minor, and diminished chords appear naturally in both major and minor scales. They can be thought of as the basic materials of scales. Any major or minor scale has exactly three major chords, three minor chords, and one diminished chord. The diminished chord is seldom used in major keys, but appears from time to time in minor keys.

Here are all examples of major vs. minor vs. diminished chords as they occur naturally in the major scale

The key of A major gives us a total of seven chords at our disposal: A, Bm, C#m, D, E, F#m, and G#°. Upper-case letters (e.g. “A” and “D”) refer to major chords. Letters that add a lower-case “m” refer to minor chords (e.g. Bm, C#m). And finally, the degree symbol (°) refers to the diminished chord.

Absolute vs. Relative Chords

Just like with individual pitches, we have absolute and relative ways of thinking about chords. Absolute ways refer to using letter names (A, Bm, C#m, etc.) and relative ways use Roman numerals to refer to these same chords. Think of it as looking at a ground plan of the apartments vs actually living in them. Here is the way to think about it:

A: I

Bm: ii

C#m: iii

D: IV

E: V

F#m: vi

G#°: vii°

And here they are in a row:

As you can see from this table, upper-case Roman numerals refer to major chords, lower-case Roman numerals refer to minor chords, and the last chord refers to the seldom-used diminished chord.

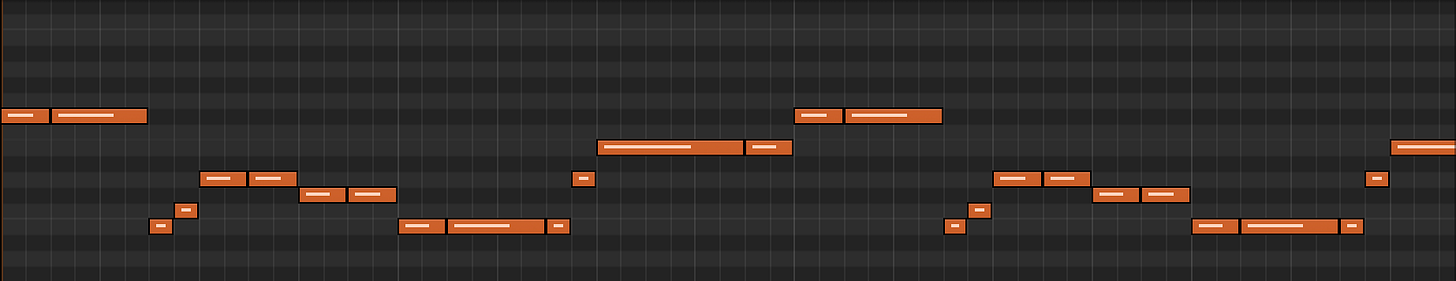

Chord Loops in "Love Again"

Okay, let’s go ahead and apply all of this knowledge to Dua Lipa’s “Love Again.” The song’s in the key of A major, meaning that any of the pitches A B C# D E F# G# are up for grabs.

The way I usually figure out what chords are used in a given song is that I listen out for the bassline (the lowest melody). Once I have picked out the lowest notes, I then infer the chords from the pitches contained in the scale the song is in. In other words, I don’t try to pick out each and every note at a given moment, but rather infer the chord notes from the context provided by the key signature (A major).

Let me give an example. Here’s the bassline that comes in right after the string intro of the song.

The pitches that fall on the downbeats of bar 17 (Beats 1 and 3 of the bassline) are: F#, D, while those of bar 18 are B, E. Now I go and convert these absolute pitches into relative names, i.e., scale degrees: 6, 4, 2, and 5. I then turn the scale degrees into Roman numerals, which converts them into chords. Here I pay attention to whether or not the qualities are major or minor (see my table above). In a major key, vi is always minor, IV is major, ii is minor, and V is major.

In pop music generally speaking, the most common chord loop is one where we have one chord change per bar. However, Dua Lipa’s “Love Again” is different, as this song has two chord changes per bar:

Bar 17: F#m (vi) – D (IV)

Bar 18: Bm (ii) – E (V)

That’s all there is to the song, harmonically speaking. These chord changes carry us throughout the song, including the more muted bridge section, where the chords are more implied rather than explicitly stated.

Thinking of this in the apartment analogy, the song occupies two large and two small rooms. This gives the chord loop a balanced feel.

I think that’s it for this week! It was fun but honestly a bit taxing to write this one. But the apartment building metaphor I came up with I’m really happy with, and I think I can re-use in the future.

Anyways — that’s it from me for this week. Enjoy some ~ pop music ~ . Charli XCX’s new album Brat is releasing on Friday, so keep an eye out for that.