A. G. Cook's Chords for "Paradise"

Part II on a series on MIDI & how to write chords in the piano roll

Some of my favorite Charli XCX songs are those early tracks she did with PC Music and SOPHIE, in the really early days, the 2015–16 era.

If I recall correctly, the earliest Charli x SOPHIE x PC Music collaborations are those tracks on the Vroom Vroom EP, released in 2016. when it came out, the EP was divisive, derided by some critics, while celebrated by others.

The EP was mostly done in collaboration with SOPHIE, as well as Swedish major label producers Patrik Berger and Martin Stilling. There is really only one track on that EP in which A. G. Cook’s chord-writing takes center stage: “Paradise.”

I don’t know about you, but I just can’t get enough of those trance stabs…

They were written by A. G., while the hard, punchy synthetic drums and the wooshy-wooshy FX come from SOPHIE.

Hearing these parts separately, I’m reminded of this passage from A. G.’s tribute to SOPHIE, which he published just after her untimely death in 2021:

We were opposites in many ways, and naturally complementary. At that time I was a total MIDI chord and preset junkie, obsessed with layering music and striving for an emotional impact, but essentially terrified of synthesis. Sophie was already a sound design virtuoso and could mould pretty much anything out of thin air, but avoided chords which got in the way of the limited space that the audio spectrum provided. We were intrigued by each other’s approaches and would trade a lot of those skills over the years, but when we worked together we tended towards that original formation, bringing elements together almost instantaneously. My chords, her sounds, done. Vocals were the component that sat on top of everything else, and we worked on those much more equally, always trying to give songs a personality beyond the sum of their parts.

Reading this passage I can’t help be reminded of the Trunks and Goten fusion from Dragon Ball Z. But I digress…

I especially like the rich and complex chord-writing on this track, and I can’t count the number of times I’ve listened to it. It is only perhaps slightly topped by the “A. G. Cook Special Edit,” which he made for an LA show later that year (?). In case you don’t know it yet, you can check it out here:

A. G. Cook’s Chords for Paradise

Ok so without further ado, let’s dive into the chord-writing for Paradise. Like the previous three articles on MIDI & PC Music, this article is quite technical, so if you have any questions, don’t hesitate to ask a question in the comments below.

I also realise this article is on the longer (and detailed) side. So if you don’t have a ton of patience, and just want the TLDR on how the chords work, here it is:

slightly vary the chord positions in the piano roll to create a syncopated rhythm,

use pedal tones, i.e. sustained notes that carry from one chord to the next,

use suspensions, i.e. triads that substitute the 3rd with the 4th or 2nd,

transpose chords up an octave or two to add extra energy.

Still with me? If you are you can follow along by downloading the MIDI titled “Paradise AGC.mid” in the 7G Deluxe files.

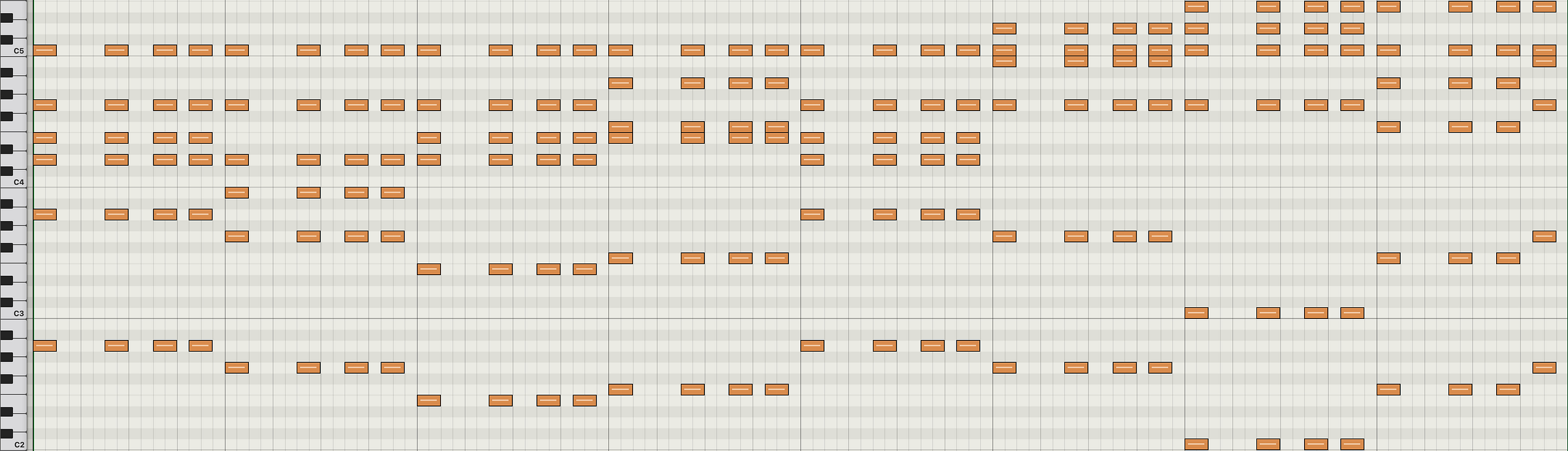

Let’s listen to the entire MIDI first. Here’s the first Cycle.

And here’s the second one:

Transposed from the original key of D major to C major for easier legibility and to make it easier to compare to other MIDI.

Ok, let’s break it down into some core components.

Syncopated Rhythm

One of my favorite parts of “Paradise” is its use of syncopation—a rhythmic technique in which notes (or chords, in this case) are placed on off-beats.

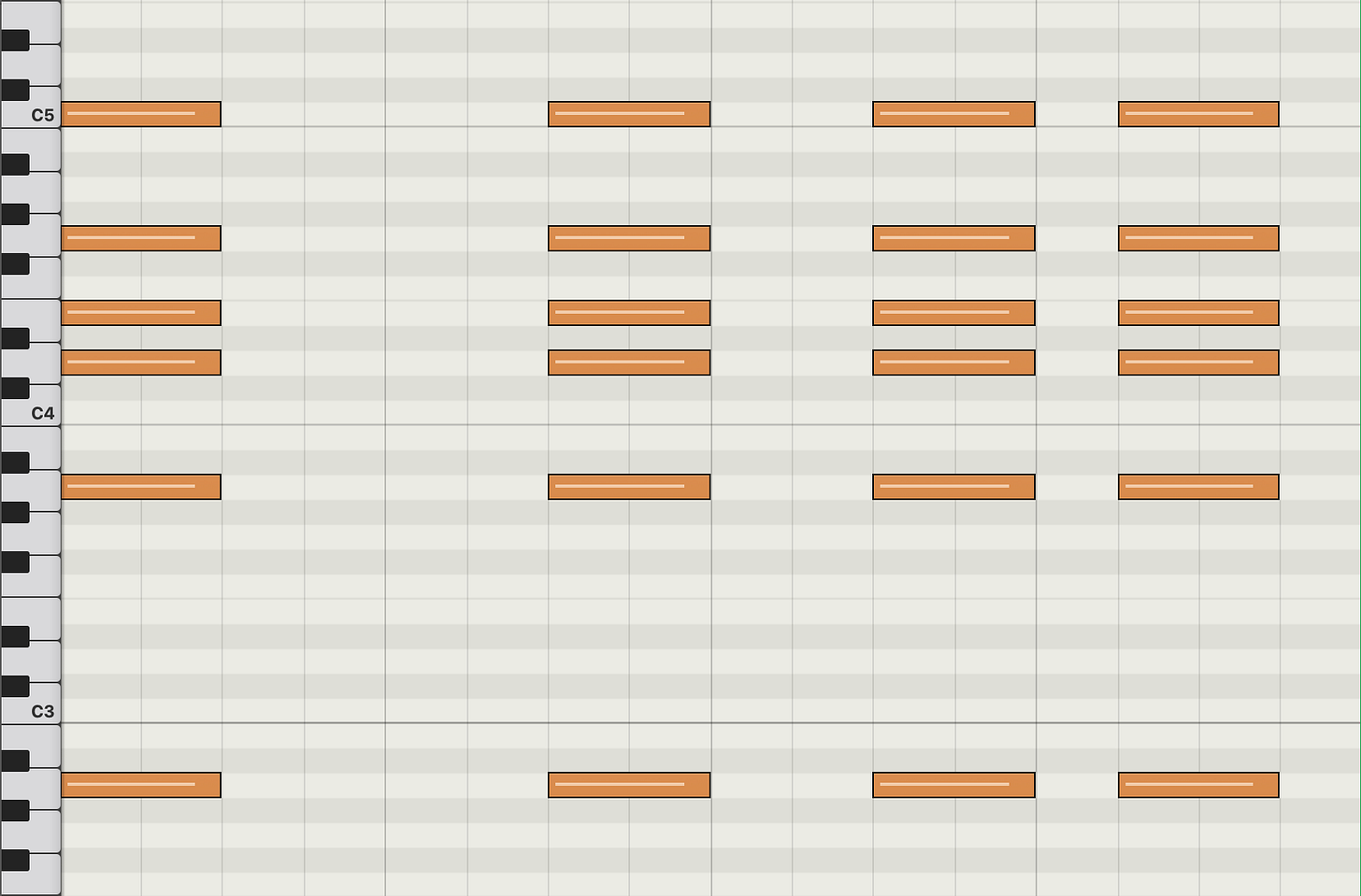

Here’s how it’s done. Let’s assume you begin with this chord:

First, break the entire chord up into four eighth notes:

As you can tell, the chords now fall squarely on Beats 1, 2, 3, and 4.

To introduce syncopation, let’s move three of the chords back a little, so that they fall on the weak (rather than strong) beats:

Then take the last chord and move it forward by a sixteenth-note:

And there you have the rhythm. Boom. Now let’s loop it:

Done!

BTW if this rhythm sounds familiar to you: it was also used in Hannah Diamond’s song “Make Believe.” AFAIK rhythms aren’t copyrighted, so I’m sure A. G. wouldn’t mind it if you used it in one of your tracks too ;)

Pedal Tones

Alright, let’s now move on to another key technique, that has more to do with the chords themselves.

In his recent interview on the Tape Notes podcast, A. G. stated that:

“I try and avoid it being this basic triad as you’d play it on a piano or keyboard.” (TN 30:00).

One core technique A. G. Cook uses to avoid basic triads is to use pedal tones to write more complex chords. Essentially, this refers to one specific degree of the scale that carries over from one chord to the next. We already saw this technique in action in my newsletters on “I.D.L.” and “Know Who You Are” by EASYFUN.

Here I’ve highlighted all the pedal tones contained in the first cycle. We can rank them as follows:

C (Scale Degree 1), highlighted in green, is contained in 9/9 of the chords

G (Scale Degree 5), highlighted in blue, is contained in 7/9 of the chords

D (SD 2, red) and E (SD 3, purple) are contained in 6/9 of the chords

If you recall, I. D. L. also used C as a pedal tone. This example is more complex as it uses multiple pedal tones in combination.

Here’s the second cycle. This time we can see that the number of pedal tones have been reduced down to two: G and C.

G (SD 5, in blue) appears in 8/8 of the chords

C (SD 1, in green) appears in 7/8 of the chords

Pedal Tones allow you to create more complex chords that use chord extensions (intervals beyond the 7th), without needing to think in terms of “I’m adding the 9th, 11th,” and so forth.

They are an elegant and straight forward technique for building complex chords.

Suspensions

A favourite technique of A. G.’s is to use suspensions. Here’s a quote from A. G. Cook’s recent interview on Tape Notes:

I also find when I’m doing chords, it has a lot of suspensions in it. I don’t use music theory a lot when I’m thinking, but I always find myself drawn to the tension of a suspended note being resolved or not resolved (TN 30:30).

Suspensions are usually dissonant notes that add tension to a chord. Let’s use the most common two examples:

A triad consists of a root note + the 3rd + the 5th. If you substitute the 3rd with either

a) a 4th or b) a 2nd, the chords become more dissonant, or crunchier.

Here are some concrete examples. You’ll first hear the standard triad (Root + 3rd + 5th), then the two suspensions (4th, then 2nd).

Now what A. G. frequency does is that he’ll include the suspension within the standard triad, that is in addition to the 3rd.

The effect this technique has is that it makes the chords even crunchier, because the 4th or 2nd clashes with the root, 3rd, and 5th.

Most of the time, suspensions are just a result of using pedal tones, which most of the time don’t form part of the standard triad. In effect they transform into suspensions, adding dissonance:

As you can see, the pedal tones of D, C, and E are functioning as suspensions, adding “crunch” to chords that would otherwise be basic triads or seventh chords.

Octave Transposition

Ok, let’s move to a final technique, which is the easiest of them all: octave transposition. The idea is that you can amp the energy by pitching up the notes, without altering the content of the chords themselves.

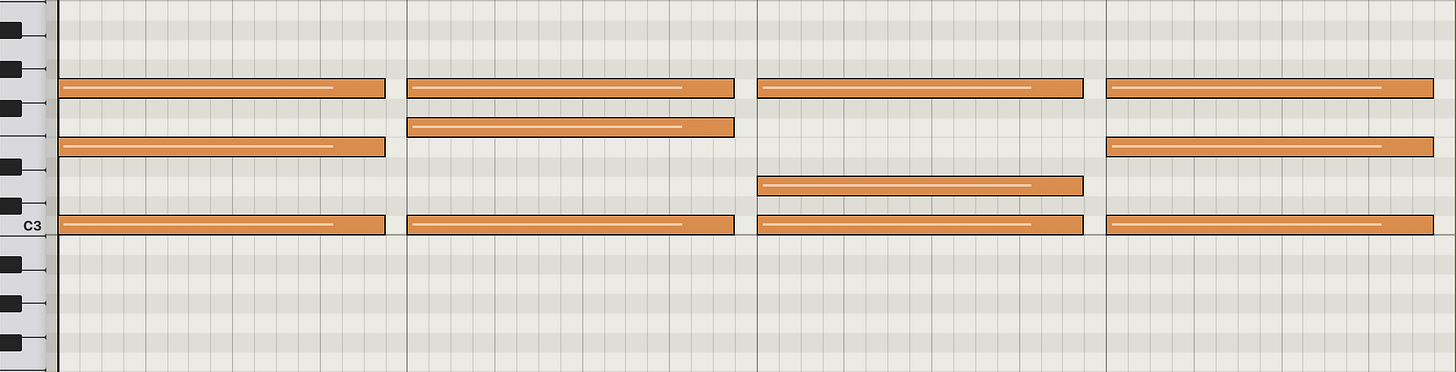

To show you how it works, let’s compare this:

With this:

Do you notice how the Cs have all been bumped up to C4 and the Gs has been bumped up to G4?

Also notice how in the first example, the chords have an ascending motion, whereas in Example 2 the highest note is consistently G?

The chords themselves are identical but the MIDI notes have been octave-transposed up to give them a more euphoric & uplifting quality.

Wrap-Up

So in a nutshell, the way “Paradise” works is via syncopated rhythms, pedal tones, suspensions, and octave transposition. That’s it.

While I understand that MIDI and chord-writing is not the most accessible of things to be writing about, I think all producers can benefit from the techniques discussed above; and borrowing them in a fairly general way can make us all better musicians (:

If you’ve made it to the bottom of this article — congratulations! Have you tried incorporating some of these techniques into your own chord-writing? Drop a comment below.